Summary:

- Contrary to public perceptions most workers (and hard working families) are not suffering a cost of living crisis as often claimed in political debate.

- The source of this widespread misconception is the national statistics which are deficient in this key area

- A failure to properly allow for the, so-called, composition effect in earnings gives a very misleading impression and puts a huge question mark over the election’s key economic statistic

- ONS commentary fails the “true and fair” test – publications are hard to find and do not explain what the figures really show

- The standard comparison does not use the best measure of earnings and uses the wrong measure of inflation

- Many of the huge number of newly created jobs are low paid so aggregate earnings in the economy are growing slowly but most workers (about 85%) are seeing very healthy real terms growth in their wages as they stay in the same job from one year to the next.

- As the numbers are hard to find and poorly explained, politicians and others deliberately take advantage of the confusion and skew public perceptions.

- The statistics board (UKSA) has ignored the issue. It is time to do its job properly.

Note: The ONS issued a statement about the 4% earnings growth on 12 March following a blog from the TUC.

The most common attack of the Labour Party in the last year, since the GDP figures started to pick up, has been that wages aren’t keeping up with the cost of living. In speeches this year, Ed Balls has said: “While growth has returned in many countries working people on middle and low incomes are still seeing wages stagnating.” And in one document wrote: “For most people in work, the spending power of wages are being eroded.”

This has become widely accepted as the truth yet it is a statistical fallacy.

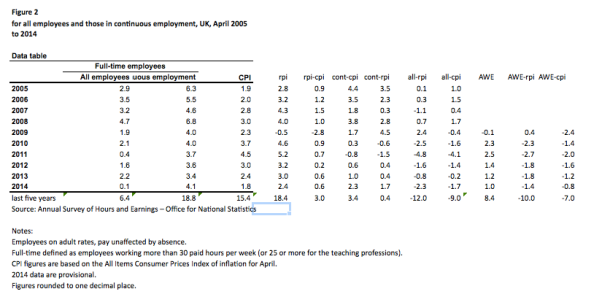

Such statements are based on taking average earnings (AWE) and dividing by RPI. (AWE – sum of last five annual growth rates – is up by 8% but RPI equivalent up by 18%, implying a real terms fall of 10%.)

But these are not the right figures to use.

ONS says: “AWE is not a measure of rates of pay or settlements …….” As ONS puts it: “AWE reflects changes to the composition of the workforce. ……. an increase in the relative number of employees in low-paying industries would cause average earnings to fall.” (See AWE in section 6 of the monthly release.)

And it should be CPI not RPI:

- RPI is no longer a National Statistic.

- Last month’s Johnson review reiterated that UKSA should not let it be used unless there was good cause. “Government and regulators should move towards ending the use of the RPI as soon as practicable”

So if these are not the figures to use, what should be used?

On inflation, it’s easy. CPI. And, as its rate of growth is lower than RPI, so the real earnings growth rate, on any measure of earnings, will be higher due to lower inflation . in broad terms, CPI growth of 15% over 5 years compared to the RPI’s 18% so real terms loss on AWE is 7% not 10% (+8 -15 = -7). For data see table 2, page 20, of this release.

On earnings, there is the ASHE survey. It is the ONS preferred measure. (And preferred over the third measure the ONS has, the LFS.) It has a long history. It is trusted. But it is only annual data so is not used as much in economics commentary even though it’s hugely popular with academics and other user types. For medium term comparisons of cost of living and earnings, such annual data is fine. These things do not fluctuate from month to month.

But, much has changed in the labour market in the last few years. Many jobs have been created at the lower end of the pay scale and jobs lost at the top end. This ASHE figure suffers from the same composition effect that the AWE data does. In this series, however, data is published to compensate for that.

The chart below was published by ONS on 19 November – the last time ASHE data was published. The dark blue line shows that median earnings have grown by less than CPI inflation for the last six years. That seems to support the Labour line that earnings have suffered in real terms.

The light blue line shows the earnings of those (84% of the total) who have been in the same job for a year or more. This is the kind of like-for-like comparison is what the ONS does for all other data (and most users would expect). On this measure, earnings growth has been above inflation in all but one year. A very different picture from that which is taken to be true.

Real earnings growth (AWE and RPI) of -10% over 5 years shifts to +3% using continuous employment in ASHE and CPI.

The normal debate about whether an average (AWE) is better or worse than a median (ASHE) is of little interest here – the real issue is allowing for composition shift.

If Labour, the media or anyone is to talk about typical families or individuals then the typical one is one that has kept their job in the last year (85% roughly depending on whether it’s p/t, f/t, m v f etc) so a measure that allows for composition is the right one. A measure that does not allow for composition might be more appropriate for macro-economic modeling (or debate about shifts between pay and profits) but that’s not how it’s being used in the “hard working families” debate.

A mini model to explain how the maths works if you add jobs at the low end of the scale ……………

The fact that, in a short period of time, so many jobs have been created and that they are mostly low paid has distorted the statistic, disrupted the trend. The effect has been to bring down the median and average earnings even if the earnings of the vast majority of workers have on average been rising much more than the rate of inflation.

The table below shows the maths. Imagine:

- 100 workers in period 1

- earnings across the spectrum

- in period 2, 10 new jobs are added at the lowest wage

- all other workers (the 100 from period 1) see a 4% rise in wages

- yet by period 2, average earnings fall and median wage falls

- headline stats look terrible yet 100 workers have a 4% increase and 10 workers now have jobs that they didn’t have before!

The ONS description of earnings trends is poor. In AWE they do not alert users to the composition effect. In ASHE, it’s the same, they focus almost entirely on the “total” earnings in their release not the one year continuous employment figure and fail to alert users to the very real pitfall. Yet the survey is described as its preferred measure of earnings.

On top of that the ONS web pages are a nightmare to navigate – perhaps why this scandal has remained hidden for so long.

It is thought that UKSA will be producing a report on this on 10 February but it is likely to be too little too late.

Issues:

- It is time for the UKSA board to demand balance in the ONS release.

- It is time for the UKSA board to correct the misinterpretation – often deliberate – in the media and political debate.

- Why has the ONS let this run for so long? It puts a huge question mark over the quality of its economic analysis – and leadership. Why do the various teams in ONS working on earnings not work together?

- Why are the earnings figures so hard to find on the ONS website? Which link on this page do you click?

- There is also a question as to why the composition effect was allowed to creep into the data when the index was revised some years ago. (It used to be the AEI until Jan 2010.) This is another sign (along with the rise of CPI and demise of the RPI) that the ONS has been hijacked by the BoE and Treasury.

“Why are the earnings figures so hard to find on the ONS website?”

Why are lots of ‘figures’ so hard to find!

LikeLike

Hello,

Does this analysis change your conclusions?

http://touchstoneblog.org.uk/2015/03/ons-now-say-that-nominal-pay-growth-is-2-not-4-per-cent-for-those-in-continuous-employment-with-real-pay-stagnating/

LikeLike

You are right to try to get some sense out of the ONS! It looks like a mess.

LikeLike

Please note another set of figures from ONS relating to those in continuos employment: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/media-centre/statements/note-on-tuc-blog—ons-now-say-that-nominal-pay-growth-is-2-not-4-per-cent-for-those-in-continuous-employment—with-real-pay-stagnating-/index.html

LikeLike

I think both CPI and RPI are fundamentally flawed and can’t be fairly applied equally across the wage spectrum.

For the lower income groups CPI is grossly under-weight for essentials such as food fuel and housing. For example The weighting for housing in the CPI figures is only 14.5%. Rent is probably the single largest outgoing for most workers say around 50% of take home pay. Partly the reason why minimum wage work is undertaken by kids living with their parents or immigrants sharing a room in a house (with 3 or 4 adults in each room.)

Salaries have a ceiling and a floor. The ceiling is the productivity of

the employee. The floor is the cost of living. When the floor rises

above the ceiling, the job can’t continue. The inflation figures should be the means for workers to maintain the value of the their labour

LikeLike

You are right. No doubt in my mind.

Thankfully the new National Statistician is trying to deal with the deep-seated and long-standing problems that were brushed under the carpet, or where ever statisticians brush things, by his predecessors. It’s brave, yes, but after years of neglect, the problems could not hidden for any longer.

Pages to look at include:

http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/user-guidance/prices/cpi-and-rpi/index.html

Click to access news-release—uk-consumer-price-statistics–a-review.pdf

Click to access executive-summary.pdf

Click to access monitoring-review-1-2015—the-coherence-and-accessibility-of-official-statistics-on-income-and-earnings.pdf

etc etc

But will anything material result from it? Really hope so, but the papers show that this is not an easy nut to crack.

LikeLike